How BioShock Infinite Influenced Brittany Cavallaro’s Muse

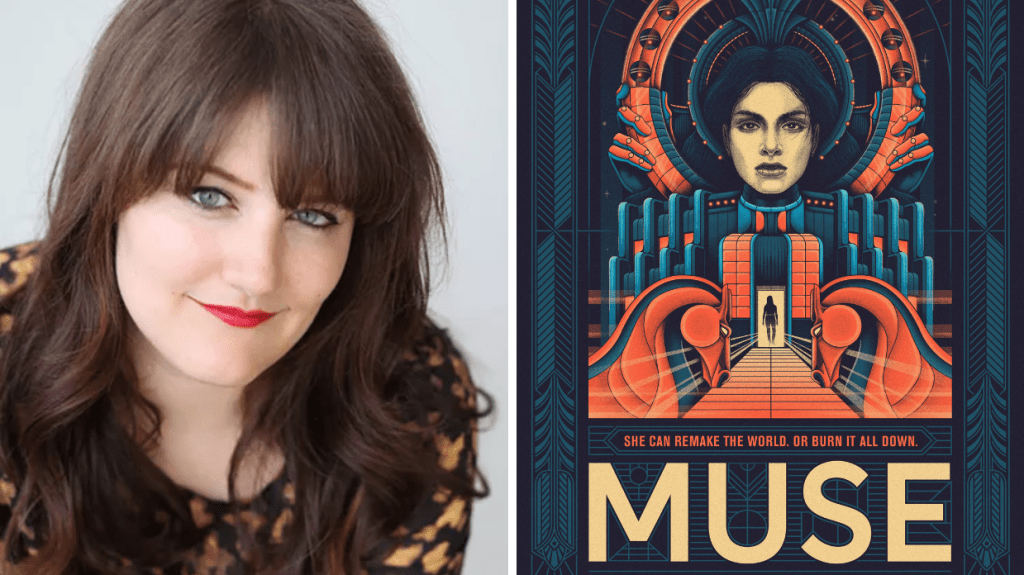

This is a guest post from Brittany Cavallaro, author of the Charlotte Holmes series and the just-released Muse, the first book in a YA duology set in an alternate history American monarchy.

The first time I played BioShock Infinite was the June when we were so broke that my then-husband started selling his plasma for money. When he wasn’t doing that, he was working as a roofer around Milwaukee while I twiddled my thumbs. I had a job lined up teaching writing that wouldn’t start for another three weeks. No temp agencies would have me. What had begun as a summer of infinite possibilities boiled down to just one: misery. In later years, we called it the Bad Summer, the capital letters always implied.

2013 was a PBR summer, a lay-flat-on-the-cold-hardwood-floor-at-noon summer while I tried to escape the wretched heat; it was the summer that the bed I’d had since childhood splintered and broke, and so we flung the mattress onto the floor. It was a summer when making things, writing things, was impossible. When you’re lost in a fog of worry, the words don’t come easy, if at all. I was a beginner back then. I didn’t know that beating yourself up over it just made it worse.

I didn’t know then that the only possible escape was escape.

It was, to be sure, a summer I didn’t buy anything new, but I had a shrink-wrapped copy of Bioshock Infinite that I’d preordered back in a less precarious time. I’d waited for the end of my semester to open it, thinking I’d have more time to immerse myself in the game. I hadn’t read much about it; I’d played the first two Bioshock games and loved them. I knew this one was a significant departure, that it took place in an America gone terribly wrong.

I won’t give too many spoilers, here. BioShock Infinite might be eight years old, but it’s a game worth approaching on its own merits. Suffice it to say that in Infinite, it’s 1912, and you’re a Pinkerton with a gun on a floating city in the sky, and that city is both terrible and beautiful, a kind of Epcot Americana for the Damned. There’s a rot in this America that dates back to its Founders. As you discover it (and the resistance against it), you find mad prophets, giant animatronic birds, snake oil potions that make you magical. You meet up with a girl named Elizabeth who has the power to tears holes in space and time. It’s one of those games that defies categorization: describing it here, it feels like the designers threw in the whole kitchen sink. Multiple realities? Sure! A pair of possibly evil, soothsaying twins, one of whom is voiced by Jennifer Hale? You got it. A hero to root for? Absolutely.

When I started playing Infinite, I wasn’t a novelist yet. I wrote stories that were, at best, eight pages long. But when I found a story I liked, I wanted to live in it. As a kid, I read massive fantasy series—my favorite were the forty-plus books that made up Mercedes Lackey’s Valdemar—and as a teenager, I only wanted TV shows that ran to seven or eight seasons. The narrative itself didn’t have to be epic, though that helped. I wanted room for the characters to grow and change. I wanted a world so real that I could tear a hole in my afternoon and climb inside of it.

And every day that June, I did. I wanted to linger in every set piece: the Hall of Heroes, Elizabeth’s beautiful prison. But the game was a first-person shooter, and while I love an FPS (and am a pretty crack shot), I found myself racing through each dazzlingly-designed backdrop, killing what felt like an endless parade of soldiers.

When I finished the game, I played it again, determined this time to smell the roses. But the game doesn’t let you do that. I dreamed about it, though. I showed my novelist friend, who didn’t play video games, cutscenes on YouTube. We watched it like a movie. I dreamt sometimes that I was in Columbia, the city above the sky.

That fall, I wrote a novel, and it had nothing to do with BioShock Infinite. It drew inspiration from another great love of mine, Sherlock Holmes—when I love something that much, I want to make art about it. I want to tinker with it, correct it. Make it into the story in my head, the one I’ve half-invented on top of the one that’s in front of me.

It took five years for me to get there. But in those years, Infinite attracted like a magnet other obsessions of mine—the 1893 World’s Fair and Erik Larson’s Devil in the White City; my teenage years roaming Chicago’s Museum Campus with no money and no plan; Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison’s current wars; my love for nineteenth century magicians (the year that both The Prestige and The Illusionist came out was like, the best year of my life). My daily thank-you to the universe that I was born in 1986 and not 1886, because I didn’t have to sit around in a crinoline praying for someone to take me seriously—and still as a white woman I would have been more privileged than most.

All writers do this, I think. We magpie. But there’s something about the complete immersion of a good video game—the BioShocks and Bioware games of this world—that makes you want to live in it. Maybe it’s because you actually are: the hands you see in front of you are your hands. The footsteps you hear are your footsteps. The decisions you make have consequences that will forever change the ending, unless you want to start all over.

I like to joke that when I game, I’m a serial monogamist. (I mean, I generally only play 80-hour RPGs! Some commitment is clearly required.) But reading is like that for me, too: when I start a book, pretty much only alien invasion will keep me from finishing it in the same sitting. I want to go in and throw away the key. I love characters I can follow down the rabbit hole, intricately embroidered settings, stories where I feel so invested it’s almost like the protagonist’s hands are my own.

In Muse, my new novel, we follow Claire, a girl in an alternate history America, one with a king and five provinces and a civil war on the horizon. It’s 1893. Her best friend Beatrix is racing the Wright Sisters to invent the first airplane. Her father Jeremiah is preparing an arms exhibition for the Fair, a spectacle he’s determined will make his name. He’s determined too that his daughter is the key to success: after his wife’s death, he’s begun to lose his mind, and he’s convinced that Claire’s touch has the power to grant his wishes—and maybe she does. There are bar fights and kidnappings and Nikola Tesla’s death ray (no, really); there’s a boy-king who thinks Claire can win him a kingdom.

And there’s a lot of love for BioShock Infinite, a world that I could slip into when mine felt like it was falling apart.

Muse is now available to buy wherever books are sold. You can find out more about Muse here. And you can find out more about Bioshock Infinite here.

The post How BioShock Infinite Influenced Brittany Cavallaro’s Muse appeared first on Den of Geek.

From https://www.denofgeek.com/books/how-bioshock-infinite-influenced-brittany-cavallaros-muse/