Hamilton: Thomas Jefferson Controversy Explained

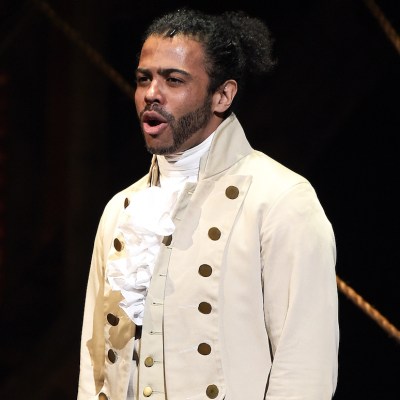

After Alexander Hamilton, no character has a bigger entrance in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical than Thomas Jefferson. For if Hamilton’s intro begins Act One, then Jefferson opens Act Two. And for those who are discovering Hamilton for the first time on Disney+, it’s a hell of an arrival as Daveed Diggs leaps across the stage with boundless confidence and swagger.

Clearly intended to be an antagonistic force, Jefferson enters stage right with an announcement that “someone must keep the American promise, you simply must meet Thomas, Thomas!” Yet even as the show depicts Jefferson as a prima donna, he is also an endearing one, draped in purple threads intentionally modeled after Prince and a glee from Diggs that’s infectious. He thus comes across as ultimately likable—and no less petty than the show’s main character who winds up dying in a duel. Jefferson is an intellectual equal to Hamilton and thereby an audience favorite. After all, Hamilton sides with this political foe over Aaron Burr in the election of 1800 for Jefferson’s overall good intentions toward America.

And yet, it’s these good, if smug, intentions that Jefferson displays in Hamilton which have come under scrutiny as of late. Because while much is made in the musical about Jefferson’s renown for writing the Declaration of Independence—which wasn’t actually well-known to the public until the 19th century—as well as his determination to protect farmers from moneyed interests, the show only lightly acknowledges his hypocrisy as a slave owner. Sure, Alexander calls him out for basking in the supposed agrarian ideals of Southern planters while willfully ignoring his paradise is built on the backs of Black slaves held in bondage. But like the real Hamilton, that hypocrisy is only used as a political cudgel during a larger argument on government. Otherwise Hamilton, and his 21st century musical, turn a largely blind eye. More upsetting still for some is how the musical characterizes Jefferson’s relationship with a Black woman he kept as property after returning from France: Sally Hemings, who was aged 16 when she got back to Monticello with the 46-year-old master.

“Sally be a lamb, darlin’ won’tcha open it?” is the lone winking acknowledgement Hemings is given by Diggs’ Jefferson. Now five years since Hamilton’s first Off-Broadway performance, this is being viewed in a different light as more Americans confront the systemic racism that’s allowed anti-Black violence to fester and be normalized for centuries.

In fact, Hamilton or not, Jefferson himself is at the forefront of this discussion with some voices calling for the general celebration of the founding father to end. Known by most products of the American education system only as the author of the soaring rhetoric of the Declaration of Independence—and it’s then-radical vision of these self-evident truths that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness”—his obvious hypocrisy on not extending those ideals to the 200 people he owned at Monticello at the time can be overwhelming. So much so, even two of his own descendants, one descended from his white wife Martha Jefferson and one from his Black mistress, and Martha’s half-sister, Sally Hemings, have recently called for the possible removal of the Jefferson’s statue at the Jefferson Memorial in Washington D.C.

Sally Hemings and Jefferson’s Thoughts on Slavery

Judging historic figures by modern social standards can often be an illusory task, but in the case of Jefferson and the issue of slavery, even he was aware of the evil inherent in the South’s “peculiar institution.” A self-styled philosopher and American thinker, his habit for analyzing and self-reflection in the mold of post-Renaissance humanism was immortalized by the mansion on a hill he designed for himself: Monticello, Italian for “Little Mountain,” sat at the center of his 5,000-acre plantation. There he’d be seen as the great Enlightenment figure pacing his balcony at dawn each morning, stewing over radical ideas about the separation of Church and State, the need for a decimal system in U.S. currency and measurements, and the swivel chair (yes, he invented it). Yet the proud man was blind to the fact that his intellectual leisure was made possible by the hundreds of Black bodies around him toiling in Monticello’s fields and picking his tobacco, or serving his guests under fear of punishment.

Still, he was aware enough. Hence a passage in the Declaration of Independence where he attempted to blame the British crown for being responsible for the slave trade in the North American colonies—South Carolina and Georgia’s delegates forced him to take it out—and the fact he proposed in 1781 that Virginia emancipate its slaves by 1784, moving them into the interior North American continent (he considered separation necessary in part because he viewed Black people intellectually inferior to whites). He even proposed in 1784 that the Congress of the Confederation (under the pre-Constitution Articles of Confederation) prohibit slavery in all future states created out of the Northwest territory. While his fellow Southern representatives defeated his proposal that year, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 made it so, preventing future states like Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan from becoming slave states.

Nevertheless, he committed what we now call rape when he made Sally Hemings a lover in France, likely when she was 14 and he was 43. It was at those ages when they met, with Hemings being sent as a companion for his daughter Polly on a voyage across the Atlantic. At the time, Jefferson had already been Minister to France for years, pursuing multiple affairs of state and the bedroom after his wife Martha died in 1781—extracting on her deathbed a promise from her husband to never marry again. But when Sally arrived in France, here was the much younger half-sister of his dead wife, a girl known by other slaves at Monticello as “Dashing Sally” because of her light skin and straight hair. Just as Jefferson would take Sally as a lover, his father-in-law John Wayles had taken Sally’s mother Elizabeth Hemings as his own coerced mistress. And Elizabeth was likewise the daughter of another white man and Black slave.

The way Madison Hemings, one of Jefferson and Hemings’ four children to survive to adulthood, tells it:

“Their stay was about eighteen months. But during that time my mother became Mr Jefferson’s concubine, and when he was called home she was enceinte by him. He desired to bring my mother back to Virginia with him but she demurred. She was just beginning to understand the French language well, and in France she was free, while if she returned to Virginia she would be re-enslaved. So she refused to return with him. To induce her to do so he promised her extraordinary privileges, and made a solemn pledge that her children should be free at the age of twenty-one years. In consequence of his promises, on which she implicitly relied, she returned with him to Virginia. Soon after their arrival, she gave birth to a child, of whom Thomas Jefferson was the father.”

As Madison’s account suggests, Sally and her brother James Hemings considered themselves free in France, and Jefferson wrote privately of them as such. So as a way to continue his physical relationship, he lured her back to Virginia where she’d officially be his property again with promises of special treatment and emancipation for their children.

At least on that count, he held true. Of their seven children, four lived to age 21 and they were freed—better than the fate of the more than 600 Black men and women Jefferson owned as property over the course of his life. The eldest two who lived to 21 before his death were given $50 and a free carriage ride to Philadelphia to live their lives among white society. Jefferson even invented a tortuous logic late in his life to argue that as they were mathematically pure and not “mulatto.”

Only Madison lived his life as a Black freedman, a fact he never appeared to fully forgive his siblings for. Of his older sister who was freed before him, Madison said, “I am not aware that her identity as Harriet Hemings of Monticello has ever been discovered. Harriet married a white man in Washington City, whose name I could give but will not.”

But it was around the time of enticing Sally back to Virginia that Jefferson became much quieter on the need of emancipation, and ultimately fearful of it. While welcoming the French Revolution to the point of self-denial about how violent and chaotic the mob became, Jefferson shuddered at the simultaneous Haitian Revolution, whereupon self-liberated Black men and women violently overthrew French colonists. He wrote to dear friend James Madison that “if this combustion can be introduced among us under any veil whatever, we have fear of it.” And as President of the United States, Jefferson and the U.S. Congress refused to acknowledge Haiti becoming a republic for Black Haitians in 1803.

Beyond Just a Declaration

Jefferson was undeniably a flawed man whose hypocrisy as the writer of sweeping rhetoric that is still cherished and quoted around the world is in direct contradiction to the Black lives he owned and often destroyed, including the 130 Black bodies auctioned off after his death to pay outstanding debts. Yet, unlike the Confederate generals deified in marble as warriors for the cause of maintaining slavery, Jefferson’s contributions are far more difficult to ignore or dismiss—both for the American experiment and the world history that followed. Because in addition to the Declaration and his ultimately damning silence on the original American sin of slavery, he contributed to many of the rights and precedents we hold dear to this day.

When Jefferson wrote the Declaration—which he penned almost by happenstance during a summer when he was primarily focused on writing the Virginian Constitution—he was considered remarkably quiet by peers like New England firebrand John Adams. That summer the slight in size, but boisterous in presence, Adams characterized the six-foot and two-inch, red-haired Virginian as a staunch advocate for independence who “never uttered more than two or three sentences” while sitting in committee. Nevertheless, Jefferson found with the pen a statement not about the right to declare war, but the right to self-govern. Historian Jill Lepore astutely notes for context in These Truths: A History of the United States that English philosopher Jeremy Bentham called it “absurd and visionary” in 1776, and “subversive of every actual or imaginable kind of Government.”

And Jefferson’s contributions extend beyond that rhetoric. While he was not present for the framing of the Constitution at the constitutional convention in 1787—he was in France with Sally—he used his pen to almost derail it, lest a Bill of Rights be added. “A bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth,” he wrote. And what he qualified as a bill of rights included protections for freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom from arrest without evidence, and freedom both of and from religion. When Jefferson colleague James Madison authored the Bill of Rights, he modeled the First Amendment on Jefferson’s Virginian Statute for Religious Freedom from 1786.

A Deist by description, and possibly an atheist by modern standards, Jefferson is more responsible than most for a new nation in the 18th century separating religion from government. The astonishment of such an idea is put into clarity when one considers that at the time of the constitutional convention, 10 of the 13 states had official state religions—and almost all states had been founded in the previous century on religious grounds. Yet Jefferson was a man who when founding the University of Virginia would build the school’s campus around a library instead of a church, as was the custom of his age.

Even before the Constitution was written without a word mentioning God, Jefferson was already warning Virginians in 1781 to avoid the trappings of letting religion dictate governmental policy. “It does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or no god,” Jefferson wrote—much to his later political woes when Hamilton’s Federalist Party tried to derail his candidacy in the election of 1800 on religious grounds. “GOD—AND A RELIGIOUS PRESIDENT,” wrote a Federalist newspaper. “JEFFERSON—AND NO GOD!!!!”

It is because of Jefferson’s lobbying that the first priority of the First Congress was to pass 10 of Madison’s 12 amendments, forming the federal Bill of Rights. Their second priority was of course to ignore petitions to abolish slavery, including one signed by Benjamin Franklin on his deathbed.

What Hamilton Left Out

On the subject of Alexander Hamilton, the musical named after him aptly demonstrates Jefferson’s folly to not see the need for a stronger federal government that can compete and trade on an international scale, yet the show leaves out Jefferson’s more pointed critique about the danger of speculation for lower-income Americans created by Hamilton’s financial plan. Indeed, Hamilton’s own corrupt assistant William Duer was embroiled in a scandal that triggered the first U.S. stock market crash in 1792. Thousands of Revolutionary veterans were ruined by the ensuing debt crisis, with one debtors’ prison in Philadelphia being so overstuffed with inmates it began publishing its own newspaper, Forlorn Hope.

In the long run, Hamilton created our modern capitalist system in the “room where it happens,” which according to Jefferson was hatched in his own private Manhattan quarters over a gentlemanly dinner and bottles of wine. But the reason to believe some version of this account is true is because Jefferson remembered it, and the 1792 crash, with woe. They were events that forced the U.S. to write its first bankruptcy laws and New York brokers to agree to a ban on private bidding—and thus the beginnings of the New York Stock Exchange.

Other elements of Jefferson’s legacy left out of Hamilton and most grade school history classes is Jefferson’s role in undoing the Alien and Sedition Acts: Laws passed by Hamilton’s Federalist Party that eventually won Hamilton and President John Adams’ approval. The new laws allowed the president to imprison and deport non-citizens without a trial and to punish newspaper printers the POTUS deemed dangerous. Yes, Hamilton came to support policies that allowed the executive branch to unilaterally diminish and exclude immigrants because he dreaded Irish transplants were sympathetic to France and Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party. Of the 25 arrests made under the new laws, there were 10 convictions. Of those 10, seven were Jefferson-friendly newspaper publishers.

It was this policy that ruined Jefferson and Adams’ lifelong friendship for decades to come and also caused Jefferson to not inaccurately view the election of 1800 as a contest between republicanism and aristocracy. The musical also leaves out that in addition to being the president who acquired the Louisiana Purchase—bringing in territory that would make up land from New Orleans to modern day Montana—Jefferson also wound up defending it from Hamilton’s other tragic protagonist, Aaron Burr.

After being vilified as the man who cut down Alexander Hamilton in a duel and fleeing as far south as Georgia, Burr decided to embrace his new status as villain and commit himself toward being what Jefferson called “an American Catiline”—the name of a Roman senator who attempted to overthrow the ancient republic before Caesar. Admittedly, the details of Burr’s plan were not fully known at his trial for treason in 1807, nor are they fully grasped today, but Burr connived with the ministers from England and Spain to sever the United States along the ridge of the Allegheny Mountains.

Consider that Burr shot Hamilton on July 11, 1804, and by Aug. 6, Anthony Merry, British minister to the U.S., sent word to London that Burr was offering his services to the British crown to help “effect a separation of the western part of the United States from that which lies between the Atlantic and the mountains, in its whole extent.” According to Jefferson biographer Fawn M. Brodie, by March 1805, Burr offered a plan to conquer New Orleans with the aid of a British squadron. And thanks to William Eaton, a critic of Jefferson nearly roped into the plot, we know Burr even planned to eventually invade Washington, take Jefferson prisoner and “Hang him! – throw him into the Potomac!” before robbing the mint and sailing to New Orleans. Burr even enlisted the aid of young Andrew Jackson and Henry Clay by suggesting his plans for the North American southwest were merely intended to steal Mexico from the Spaniards and aid the Jefferson administration.

The British and Spanish turned Burr down, though he still lied about their aid as he attempted to orchestrate an armed invasion of New Orleans in December 1805. Instead he was arrested and brought up on treason by the government, with the gallows’ rope as his final reward. And honestly, Jefferson’s former vice president would’ve probably hanged if not for a typically brilliant political performance in the courtroom by Burr and a sympathetic ear from Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall… Jefferson’s cousin and estranged political foe who invented judicial review in large part as a check against Jefferson.

Facing a Complete Legacy

Jefferson lived a life full of great historic achievement and heavy moral failing. On some level he knew slavery was America’s original sin but couldn’t divorce himself from the institution any more than he could let young Sally Hemings live free in Paris. But even in his remote mind, he was aware of the inescapability of human fallibility. Consider the Alien and Sedition Acts ended his friendship with Adams, a man he came to love during the summer of 1776 and then as fellow foreign ministers in Europe during the 1780s. Yet they then renewed their affection in 1824 after Adams’ son ascended to the White House.

Decades of acrimony and a sense of betrayal gave way to old camaraderie and intellectual admiration in their extensive correspondence over the next several years. Their letters were so heartfelt that each was apparently on the other’s mind when they died on the exact same date: July 4, 1826. Fifty years to the day that the Declaration of Independence was ratified, Jefferson died in the afternoon, surrounded by Black faces he never freed, and Adams passed in the evening. The latter incorrectly whispered as his final words, “Thomas Jefferson still survives.”

But he did not. Nor did the familial bonds of the Black men and women who served him best. In his will, Jefferson freed only five slaves, all of whom were relations to Sally, including their two other children who still hadn’t reached the age of 21. But while Sally was permitted to discreetly disappear to nearby Charlottesville without being mentioned in the will—keeping Thomas’ eyeglasses as the sole memento of a man she lived with over 35 years as more than a servant but less than a wife—the other 130 slaves left in Jefferson’s possession were sold off to the highest bidder in an auction designed to settle his sizeable debts. Unlike George Washington, who belatedly emancipated his slaves in death, Jefferson would find ways to deny freedom to the Black bodies around him, separating families among as many as seven or eight slave owners.

One such life he ruined after his last gasp was Joseph Fossett, Sally’s cousin and Jefferson’s enslaved blacksmith. Jefferson freed Joseph in his will, but the man’s oldest child had already been given to Jefferson’s grandson as a present. As for Fossett’s wife and six other children, including three daughters, they were all auctioned off. Fossett was able to raise the money to buy back his wife and he thought a son, but the owner reneged on the deal, leaving Joseph and wife Edith to retreat to Ohio for the rest of their days—a state arbitrarily made free by one of Jefferson’s other, more benevolent ideas.

Jefferson is a man made up of immense contradictions and a moral paradox as jarring as the one in the nation he helped found. His brightest and most passionate ideas are the kind we still cling to, protecting protestors from further abuse by corrupting forces in the government, just as his sins helped pave an enduring path forward for Black marginalization, abuse, and ultimately institutionalized violence. Both are part of the full picture of the man, and it’s an image I personally do not think needs to be torn down. Jefferson himself loathed the idea of venerating the founders, writing in 1816, “Some men look at constitutions with sanctimonious reverence, and deem them like the ark of the covenant, too sacred to be touched. [But] They ascribe to the men of the preceding age a wisdom more than human.”

Yet Jefferson’s visage, warts and all, is in many ways the face of America. He helped create a government that in pursuit of a more perfect Union was able to end the vile and insidious institution Jefferson personally profited from. And in the process it aspired closer to these self-evident truths Jefferson immortalized as the pursuit of happiness. Showing both sides of that legacy, including learning stations, plaques, and even statues of the people he owned, and the woman he tried to hide from history’s eyes, at his monuments is a better way of learning our full history… instead of trying to sweep it under the rug.

The post Hamilton: Thomas Jefferson Controversy Explained appeared first on Den of Geek.

From https://www.denofgeek.com/movies/hamilton-thomas-jefferson-controversy-explained/